The period of Reconstruction spanned from 1863-1877. Particularly in the former Confederacy, it was a time for African Americans to cope with the trauma of the war and their monstrous past of slavery while also learning to live under their newfound rights within the constitution. Complication arose within this immediately, because power was still held in the hands of those who had it before and during the Civil War. Nearly every attempt made by African Americans to move into the life that they had been more or less promised was unashamedly shoved back down under the hand of the most privileged. Representational artwork of African Americans became a free outlet for artists to express and oppress simultaneously through visual culture. Though excessive by no means, more African Americans were the main figures in American artwork than ever before in this time. Artwork from this period proves to be a direct commentary on deep complexity and many facets that were lived through during Reconstruction. Artists such as Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins produced beautiful outlying pieces that portray subjects of color in a fully humane and realistic way. In contrast, the most common artworks of the time exist largely in the realm of cartoons and magazines that in essence portray African Americans as “other”, subhuman, or

ridiculous, in a variety of ways. While on the surface reconstruction was intended for positive ends, deep issues and the perpetuating of racism was still occurring rampantly and unashamedly. The

purpose of this show is to open the viewer to seeing the inconsistencies found

within representational art of African Americans produced during reconstruction and how culture strongly mirrors that in both the noble and the undignified.

Winslow Homer, Dressing for the Carnival, 1876,

Oil on Canvas, 22.220.

Through its use of color and endearing figures, this painting of a family dressing in traditional Jonkonnu festival wear shows a realistic bodily representation of an African American family. The eye of a modern viewer may be jaded to the apparent normalcy of a painting such as this, but the reality is that in this time, one year before the technical end

of reconstruction, art that portrayed African Americans in such a

normal way would have been virtually unheard of. With this knowledge, the viewer suddenly sees this painting as a stepping stone for something beautiful- the recognition of the humanity that these figures posses, although still bound in harmful ways to slavery. Homer manages to stay away

from caricaturing these figures without making the figures of color appear fake or flat.

John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman,

1863 and cast 1891, Bronze, 1979.394

This heroic and stern sculpture is a unique take on freedom. The man's gaze is set hard on something in the distance, perhaps something unexplored such as great hope for the future. His back is

bent simultaneously bent as if his body is still reeling from the weight of his past and potential weight of his future. The poignancy of this sculpture is that the figure is deeply dignified. In light of past sculpture, this man is revolutionary in his resistance to classicism and his ability to exist as a whole man independently here. Only the tree stump remains beneath him, his shackles are broken, and he is ready to move into something better. This is the hope of the post-Civil War era.

Thomas Eakins, The Dancing Lesson, 1878,

25.97.1 Watercolor on off-white wove paper.

A simple and innocent composition, this painting depicts a scene that is nothing out of the ordinary. Painted only one year after Homer's Dressing for the Carnival, it resembles that painting in its ease with which the figures are depicted. They look natural and utterly themselves rather than what a white man would like to imagine they look like. As a result, this piece represents freedom in a way that permeates the very smallest corners of life. With this freedom though, comes a strange twist upon further inspection. The left hand corner features a framed photograph of Abraham Lincoln. Perhaps this was used to shed light on the prominence of their emancipation. It would be ignorant to not note that it also shows their dependence on the white president. While fine in theory, this has dangerous implications for how art at the time was training black and white citizens alike to thing about the reasons for their freedom.

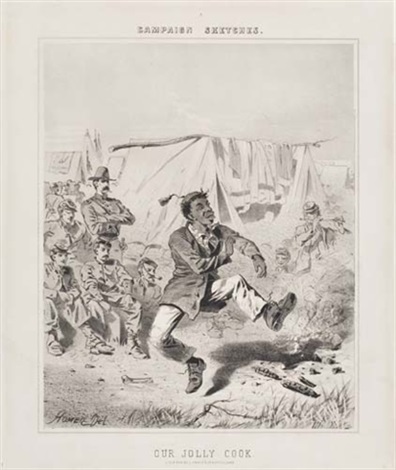

Winslow Homer, Campaign Sketches: Our Jolly Cook,

1863, Lithograph, Cleveland Museum of Art.

In stark and ugly contrast to the previously lauded artwork of Homer and Eakin's artwork, this sketch flies in the face of the truth of image bearing that each African American holds. Here we see a black man performing a seemingly outrageous dance for a host of white soldiers. While these men are composed in the background, the cook takes center stage with his goofy hat, flailing limbs, and excessively protruding facial features. In reality, everyone should be able to acknowledge that African American men do not look how the jolly cook is portrayed. A prime example of the complexity found within reconstruction, we see here that Homer is not immune to the snare of oppressive cartoon commissions, and carrying those out unashamedly. Viewing these artworks with the knowledge that they came from the same man creates cognitive dissonance between what the truth should be (and in some cases is), and what exists just as fully on the dark side of that truth.

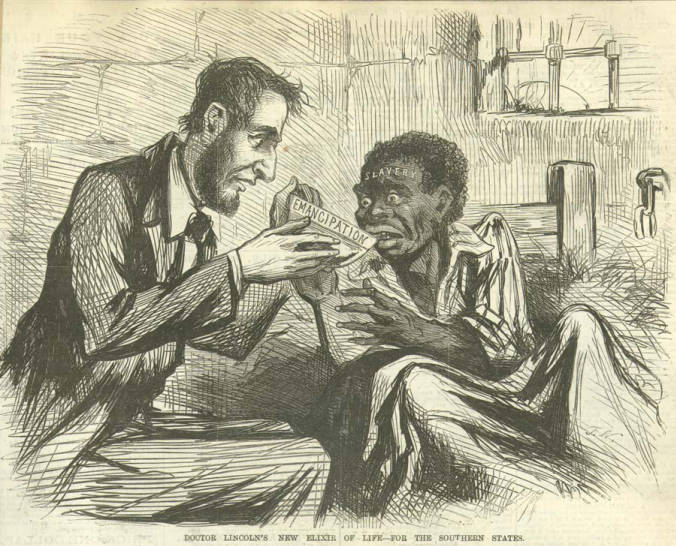

Thomas Nast, Doctor Lincoln’s New Elixir of Life- For the Southern States,

1862, Cartoon, Harper's Weekly.

Nast's sketch here does not stand alone in the visual commentary that shows freedom on a surface level, but pushes them down under the hand of white men again and again. Regardless of what kind of political statement Nast was attempting here, the universal concern is how the nearly-liberated slave is portrayed. Much of the truth of the glory of emancipation that he could have tried to communicate automatically is absolved within his blatant misrepresentation of African Americans through the ape-like portrait of this man.

Davis Milling Company, Aunt Jemima Advertisement,

1893, Newspaper Print.

The familiar franchise is recognizable across the United States, Genders, and social classes. Aunt Jemima brings association of slow Saturday mornings and family camping trips. The fond memories associated here are only possible through the objectifying of real people who were used as models for early advertisements and promptly forgotten in the recreation of who they are. From the loose use of Ebonics to the uneven proportions of Aunt Jemima's face to the rest of her body, this photo screams disrespect. But accomplished under the guise of an innocent pancake mix ad, racism was allowed to be perpetuated freely on the shelves of grocery stores and in kitchen pantries for decades upon decades. Published nearly 20 years after the technical end of reconstruction, the wounds that the United States tried to erase are shown here to still be buried deep within.

Thomas Worth, Currier and Ives,

Darktown Yacht Club-Ladies Day, 1896, Lithograph.

Darktown was a fictional community

that became wildly popular and found itself in mass demand from the public.

Yacht clubs are supposed to be fun and the woman has come to enjoy her day, but

instead she is embarrassed publicly for trying to do exactly what she was told

she could. We know realistically that no person would be this size. Racism

often is masked to be discreet and appear unintentional, but the Darktown pieces

show more than perhaps anything during this period that care for African

Americans was the absolute least of these artists concerns. We see here a

blatant jab at African American Women, unlike the men that have been

highlighted in this show's other pieces. A host of issues that all arise from

misconceptions of black women and their bodies were given through this artwork like handouts to consumers who chose lies over truth for decades on end.

No comments:

Post a Comment