Women in bustles and top hat crowned men populate the Paris streets and country gardens of the Impressionists’ canvases. To us, their paintings seem old-fashioned and traditional, suitable for hanging in the living room or putting on a greeting card. However the Impressionists were portraying an exciting new Paris, full of building projects and changing social dynamics. Both their subject matter and their method of using cropped compositions and visible brushstrokes was fresh and modern.

One distinctive aspect of the mid- to late 1800s was the appearance of a middle class. With the middle class’s emergence and the advent of the weekend came opportunity for leisure activities. From urban cafes, operas, and dance halls, to country or seaside retreats, the Impressionists and other French painters immediately before and after them portrayed this aspect of contemporary life. Their use of light and composition reinforced the modern nature of their subject matter.

As in all their work, the Impressionists’ paintings of middle class leisure pursuits vary widely. Not only do the settings and activities themselves vary, but the artists display different attitudes toward modern life: some portray the middle class in a romanticized, idealistic way, while others portray the seedy side of Parisian nightlife. Post Impressionist painters especially moved beyond the Impressionists’ optimism about modernity, painting grimmer scenes of middle class life.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, 1876

oil on canvas, Museé d’Orsay, Gustave Caillebotte bequest, 1894

Renoir’s happy crowd of leisure-seekers is tranquil and pleasant. He portrays a crowd of working class men and women innocently dancing and talking. His palette of blues broken by green, pale yellow, and peach is cool and soothing, while the composition guides viewers through the crowd. The scene gives no hint of prostitution, poverty, or ennui. The painting serves as a record of pleasant Parisian pastimes, and its subject matter, color scheme, and frothy brushwork echo the idyllic gardens and lovers of the eighteenth century painter Watteau.

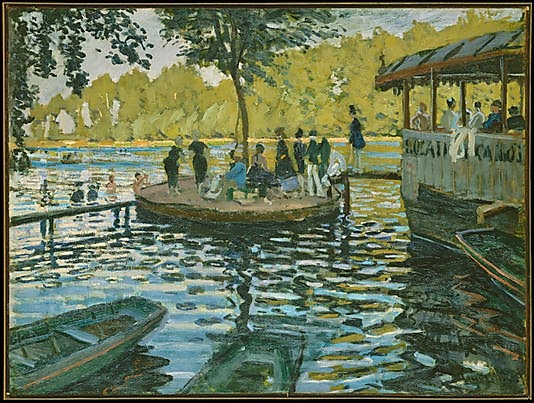

Claude Monet, La Grenouillere, 1869

oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.112

While Dance at the Moulin de la Galette focuses on interactions between people, La Grenouillere places more emphasis on the setting of sunlit trees and gently rippling water. The figures at the resort on the Seine are small with little detail; the sunny background trees and the patterns of dark green shade and blue highlights on the water are the main concern of the piece. The quick brushwork of the trees and the sketchy figures emphasize that the painting captures the feeling of one moment in a sunny afternoon. Claude Monet, Women in the Garden, 1866

oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay

Several women relax in a pleasant garden, gathering flowers. Sharp distinctions between sunlight and the shadow cast by the foliage stand out, as do the women’s dresses. Monet appears to have paid great attention to recording the details of the women’s garments. The availability of ready-made clothing enabled even the middle class to follow the latest fashion trends; like leisure time, fashion was no longer restricted to the rich. Impressionists documented these changing trends, another aspect of modernity. The Metropolitan Museum of Art quotes Manet declaring that “the latest fashion … is absolutely necessary for a painting.”

Mary Cassatt, In the Loge, 1878

oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 10.35

Like Monet’s Women in the Garden, Cassatt focuses on a female subject; however the type of leisure activity depicted is different in a meaningful way. Rather than depicting sheltered women in a garden, she explores the expanding opportunities modernity was making available to women. Women were freer to enjoy leisure activities than before. Cassatt depicts this changing social reality by portraying an apparently respectable woman alone in a theater box, using her opera glasses to survey other audience members. Edouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergere, 1881-2

oil on canvas, The Courtald Gallery, Samuel Courtauld Trust: Courtauld Gift, 1934

Although Manet did not identify himself as an Impressionist, he influenced the movement and shared their concern with portraying modernity in a fresh way. In Bar at the Folies-Bergere, Manet delves into the seedier side of the middle class’s leisure pursuits. He uses the device of a mirror in the background to reveal the crowded music hall, where men often met prostitutes. The barmaid contrasts with Renoir’s happily chattering women as she stares impassively at the viewer. Manet moves away from Renoir’s happy pleasure-seekers lit by soft natural light to artificially lit opera houses and music halls with less innocent occupants. His inclusion of artificial light draws attention to the fact that this new technology extended the possibilities for pleasure-seekers: no longer limited by daylight, people were able to stay out late frequenting music halls and mingling with prostitutes.Vincent van Gogh, Night Café, 1888

oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, 1961.18.34

As one of the Post Impressionists who were disenchanted with the Impressionists’ vision of modernity, Van Gogh takes Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergere a step further. His café is distinctly seedy, lit by harsh electric light. Like Renoir and Monet, he uses color and brushstrokes to enhance his subject matter, but his effect is the opposite of theirs. The garishly colored brushstrokes almost vibrate, imbuing the canvas with a taught, wakeful energy. The glaring lights and dark, huddled figures create a feeling of alienation, implying that modernity allows one to be in a city full of people and still be isolated. Not everything about modernity is as pleasant and carefree as Renoir’s paintings suggest.Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Moulin de la Galette, 1889

oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.458

Thirteen years after Renoir’s painting, the Post Impressionist Toulouse-Lautrec presents a sharply contrasting picture of the Moulin de la Galette. Men and women still dance and talk; even the composition references Renoir’s piece, but the atmosphere has changed. The colors are dingy and scratchy lines replace Renoir’s ephemeral brushwork. Dappled sunlight has given way to a grimy interior. The foreground figures watch the dancing couples rather than engaging with each other. They are alienated from the crowd and from each other, and the viewer looking over their shoulders feels isolated. Toulouse-Lautrec’s portrayal of middle class leisure activity is jaded, suggesting that modernity is not as rosy as Renoir and Monet seemed to think.

No comments:

Post a Comment