This comparative exhibit explores the presence of innocence and evil, and how these seemingly juxtaposing qualities unite through symbolism. The Symbolist movement shaped art and literature, especially in France, beginning in the late 19th century. It sought to express reality through symbolic means, paralleling truth without explicit representation. Common themes of Symbolist paintings include idealized women, pessimism, and dreams.

In each of these paintings, the female body is used to symbolize innocence, evil, or a synthesis of both. From the harsh strokes of Munch, to the misty blending of Morgan, to Redon's dreamlike setting, each artist interpreted the symbolic possibilities of the female form to express emotion and make sense of the innocent and the evil.

In a world situated at the precipice of the first World War, the paintings sway between despair and delight. Some express the frantic anxiety that death would soon choke victory. Others crack into the innocence of hope, magnifying where that hope is found. Some hold innocence and evil in suspension together, showing how humans are capable of both beauty and destruction.

These contrasts meet in the symbol of woman. Embodying vulnerability and strength, piety and power, the women of these paintings are drawn between myth and muse. Organized chronologically, they magnify the limitations of our attempts to explain evil, and what it means to bear the burden of innocence.

The Death of Marat, Edvard Munch, 1907, oil on canvas, The Munch Museum

The Death of Marat II squarely places woman as the source of evil and anguish. Inspired by Jacques Louis David’s 1793 painting that depicts Jean-Paul Marat, a revolutionary who was murdered by a woman during the French Revolution, Munch shows the male as an honorable sufferer, victimized by the evil whims of woman, implying that she is the source of his suffering. Though each figure is rendered with a degree of vulnerability, as both are nude, the woman is presented as ominous and powerful, standing before the wounded and immobile male. The thick lines and expressionless face of the female further the painting's unsettling tone.

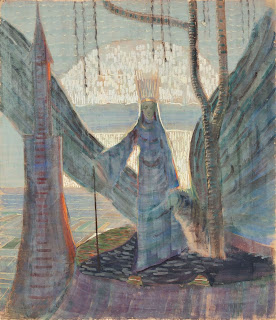

Fairy Tale. Painting III from triptych, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, 1907, tempera on paper, M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art

The Lithuanian painter Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis depicts a victoriously ominous female figure. Emerging from the shadows, the queenly woman’s blue dress stands in contrast to the bright sun behind her. However, upon closer inspection, her face has an almost dreamlike expression. Her smile is gentle; not grave or menacing, but rather detached and peaceful. In this painting, woman is mysterious. Her intentions and posture are unclear. Her form does not imply evil, but it does not imply innocence either. Often authority comes with a cost. Čiurlionis situates the viewer in an ethereal world where our understanding of the figure’s story is incomplete.

The Rape of Persephone, Rupert Bunny, 1913, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Australia

Painted with vivid hues, The Rape of Persephone is an emotionally intense piece. Rooted in the mythological world, the painting conveys agony and instability. The fight between good and evil is more distinct, with Hades rendered with deep dark purple and green clothing, and Persephone and the other women in bright colors, evocative of springtime. The painting throbs with pain, as fainting Persephone is firmly gripped by Hades, and the women surrounding her scream and cower. Woman is vulnerable. Her innocence can be exploited. The evil world will try to consume the innocent.

Virgin, Gustav Klimt, 1913, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Prague

Virgin coalesces dizzying colors with pale flesh. The jewel tones and whimsically patterned fabrics drape and trace the female figures’ skin. The tone is peaceful as they rest and doze. In this painting, innocence is suggestive. The title suggests purity, but the provocative poses of the female figures do not. Here, the female forms in this piece symbolize innocence through their vulnerable purity. Seemingly unaware of the viewer, woman’s innocent ignorance is prized and portrayed as beautiful.

The Prayer, Felice Casorati, 1914, tempera on moleskin, Galleria d'Arte Moderna Achille Forti

In Felice Casorati’s painting, a woman kneels in prayer. The cool blue plane of sky makes space for the expanse of grass, dotted with stems and flower buds. The still scene centers on the pious woman in prayerful contemplation. Though surrounded by beauty, her eyes are closed, blocking out the visually rich world surrounding her. In this solitude, her piety perpetuates innocence. Woman’s action is a symbol of hope. There is still a reason to pray.

Pandora, Odilon Redon, 1914, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 60.19.1

Pandora is a poignant product of its time. Painted shortly before the dawn of WW1, the painting juxtaposes peace with chaos, as the mythical woman unleashes the world’s fate. Similarly to Munch’s piece, Pandora presents woman as the reason for suffering. The nude female figure cradles the box, merging innocence with destruction as she begins to lift the lid. Once the box is open, evil will emerge. In this dreamy world where flowers bloom and grow in abundance, Pandora holds the fate of the world in her hands.

S.O.S., Evelyn De Morgan, 1914-1916, oil on canvas, De Morgan Collection

S.O.S. is the sole painting in this collection attributed to a woman. This piece is indicative of the global turmoil of WW1. As winged, fire-breathing sea monsters nip at the heels of the female figure, she lifts up her hands and head toward the sky. The woman, standing as a symbol of peace, does not fight back. Instead, she raises her arms in an orant style pose. Unharmed by the forces of evil, she stands as a bright beacon for good in an otherwise hopeless situation.

Song of Bohemia, Alphonse Mucha, 1918, oil on canvas, Mucha Museum

The final painting, Song of Bohemia, presents another dreamlike setting. The radiant figure in the foreground tilts her head back, soaking up the sun. Pastel flowers laced into wreaths are spread across her long white dress. The scene evokes a sense of celebration and denouement, being completed by Mucha at the close of WW1. The bright sky bathing the green hills in light suggests the stillness of a sunny day, and the female in the center rests in complete peace. Her innocence reflects the restoration of her country.

-Stella Owen

References

“Fairy Tale. Painting III from triptych.” Google Arts and Culture. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/fairy-tale-painting-iii-from-triptych-m-k-%C4%8Ciurlionis/5AG9ROyI_-XM4Q.Groom, Gloria and Stevens, MaryAnne. Redon: Prince of Dreams, 1840–1916. Edited by Douglas Druick. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1994.

Myers, Nicole. “Symbolism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/symb/hd_symb.htm.

“Pandora.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437383.

Schubert, Gudrun. “Women and Symbolism: Imagery and Theory.” Oxford Art Journal 3, no. 1 (1980): 29–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360176.

“Song of Bohemia.” Google Arts and Culture. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/song-of-bohemia-alphonse-mucha/9QEdKFey12i7-Q.

“S.O.S.” Google Arts and Culture. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/s-o-s-evelyn-de-morgan/xwEnx2HsNtDV3A.

“The Death of Marat II.” Google Arts and Culture. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/the-death-of-marat-ii/AgHihh4p4aGqNw.

“The Prayer.” Google Arts and Culture. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/the-prayer-felice-casorati/pgEZV1rIUpMxIg.

No comments:

Post a Comment