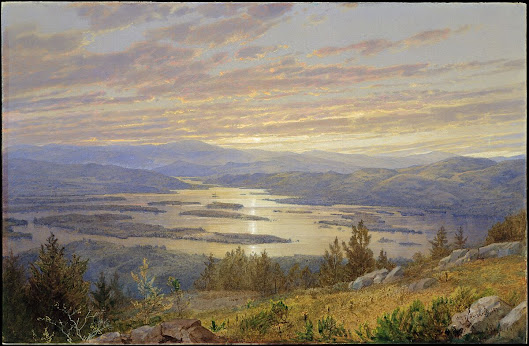

The Western tradition of landscape painting has experienced many iterations over the centuries, but many traits have remained the same – the painting is often divided in thirds, with land, sky, and water filling the space horizontally. Perhaps a desktop wallpaper is called to mind, or the logo for an outdoor equipment brand. Landscapes are so familiar to us that it may seem odd to describe such a painting as dramatic, momentous, or dynamic. However, with close examination to the techniques used in 19th century landscape painting, a viewer can come to appreciate the innumerable stylistic variations within a seemingly straightforward genre. William Trost Richards’ Lake Squam from Red Hill, painted in 1874, is an excellent example of this – by drawing from the detail and precision of British Pre-Raphaelitism, the Luminist attention to the particularities of light and atmosphere, and the majestic wilderness portrayed by members of the Hudson River School, Richards creates movement within stillness, and immense depth on a flat piece of paper. This curation will lead you through various artists and styles that inspired Richards’ watercolor, and bring you to a fuller understanding of the pieces that go into landscape painting.

John Ruskin, Amboise (c. 1840-45)

Watercolor on paper, 15 ¼ x 11 ¼ inches.

Private collection.

John Ruskin was a British artist and art critic who held immense influence in the art world, especially due to his outspoken support of the controversial Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This painting, as the oldest one in this collection, still finds its roots in Romanticism, as seen through the mysterious translucence of the rocks, castle, and sky. The gestural softness within such a grand scene evokes the sublime, comparable to Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Though Richards did not draw directly from Romantic qualities, he was trained by Ruskin’s books and criticism, and thus the emotion of Romanticism is evident in Lake Squam from Red Hill. Both Ruskin and Richards employ atmospheric perspective, glazing large portions of their watercolors in a misty blue to build a real, dramatic depth.

John Everett Millais, Ophelia (c. 1851-2)

Oil on canvas, 30 x 44 inches.

Tate Britain.

Though formally different from Ruskin’s work, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was staunchly defended by him. This group of students intended to revive painting by studying Italian art before the era of Raphael, in which they observed a unique freshness of emotion. Millais’ painting is an excellent example of the Pre-Raphaelite dedication to detail and botanical accuracy, as well as their distinct vibrancy of color. Their ability to capture the precise nuances of light and nature was largely due to their innovative plein air technique, which reads very clearly in this painting; the grassy bank seems to come beneath and around the viewer. Richards achieves a very similar effect in Lake Squam from Red Hill, as the foreground depicts Red Hill’s hardy shrubbery and wild grasses, among which Richards likely stood.

William Trost Richards, Sunset on the Meadow (1861)

Oil on canvas, 20 ¼ x 27 inches.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The technical rigor of this oil painting marks Richards as an American Pre-Raphaelite, and informs the choices he makes in Lake Squam from Red Hill. Though darker than Millais’ Ophelia, the colors in this painting are very saturated, and the intricate blossoms pop out against the greenery. In fact, the attention to lighting is characteristic of 19th century landscape painting, echoing Luminist tendencies. No details are simplified here, in the way that we see Ruskin’s trees and rocks simplified in Amboise. Instead, each individual leaf and stem is visible, immersing the viewer in the lush, thriving environment.

Thomas Cole, The Hunter’s Return (1845)

Oil on canvas, 40 ⅛ x 60 ½ inches.

Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

John Frederick Kensett, Lake George (1869)

Oil on canvas, 44 ⅛ x 66 ⅜ inches.

15.30.61

Edward Church, Twilight in the Wilderness (1860)

Oil on canvas, 40 x 64 inches.

The Cleveland Museum of Art.

William Trost Richards, Lake Squam from Red Hill (1874)

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on light gray-green wove paper, 8 ⅞ x 13 9/16 inches.

80.1.6

%20--%20PRE-RAPHAELITE,%20note%20botanical%20accuracy.jpeg)

%20--%20HUDSON%20RIVER%20SCHOOL%20FOUNDER.jpg)

%20--%20HUDSON%20RIVER%20SCHOOL.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment