Your laptop login screen. National Geographic documentaries. The nameless farm scene behind the receptionist’s desk. Every day, we visit countless landscapes through the portal of a picture frame. While many of these landscapes are photographs of real places, many more are paintings that capture the artist’s perception of that place. Some are even entirely fictitious. Yet with every new landscape we see, we are reminded that nature is one big beautiful blank slate. Right? Several artists of the 1800s would beg to differ. Their landscapes show that nature is much more—that natural scenes can also convey meaning specific to the artist. This was a controversial idea, one that would eventually upset the contemporary hierarchy of painting genres (which landscapes happened to be near the bottom of).

What follows is a collection of various landscapes of the nineteenth century. Each carries meaning differently as it reflects the sentiments and beliefs of its artist. By the end, you will be prepared to look for meaning in places you may have never thought of before.

Art is not made in a vacuum. Rather, art is infused with meaning—to be meaningful is to bear the image of God. As you look at each of these paintings, think about how the artists exercised their creative abilities through the creation of meaning.

Théodore Gericault, Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct (1818)

Oil on canvas, 98.5” x 86.5”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.183

Although this painting by Gericault is reminiscent of the Mediterranean countryside, the setting is imaginary. The bathers below and the golden light shining across the scene lend tranquility to the scene, but the ruins in the midground, combined with the encroaching dark clouds of night, remind us of the cyclic rise and fall of empires. This painting was originally intended to be one of a set of four, where each painting portrayed a different time of day. It may be that Gericault is connecting the times of day to the seasons of life and to the seasons of civilization.

Camille Corot, Hagar in the Wilderness (1835)

Oil on canvas, 71” x 106.5”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 38.64

For Corot and other painters of his time, landscapes were not complete without human figures to bring meaning to the scene. In the familiar Bible story of Hagar and Ishmael, faithfully retold here, we can see just how powerful the addition of figures is: what would otherwise be a placid, comforting scene is transformed into an arid wasteland when we realize the mother and child are dying for lack of water. The desperation of the mother’s heavenward gaze over her child’s already-lifeless body directs us toward the expansive sky, where we see an angel coming to rescue them. Corot’s particular use of landscape here is purposeful—here, it serves as the irreplaceable setting for a spiritual lesson.

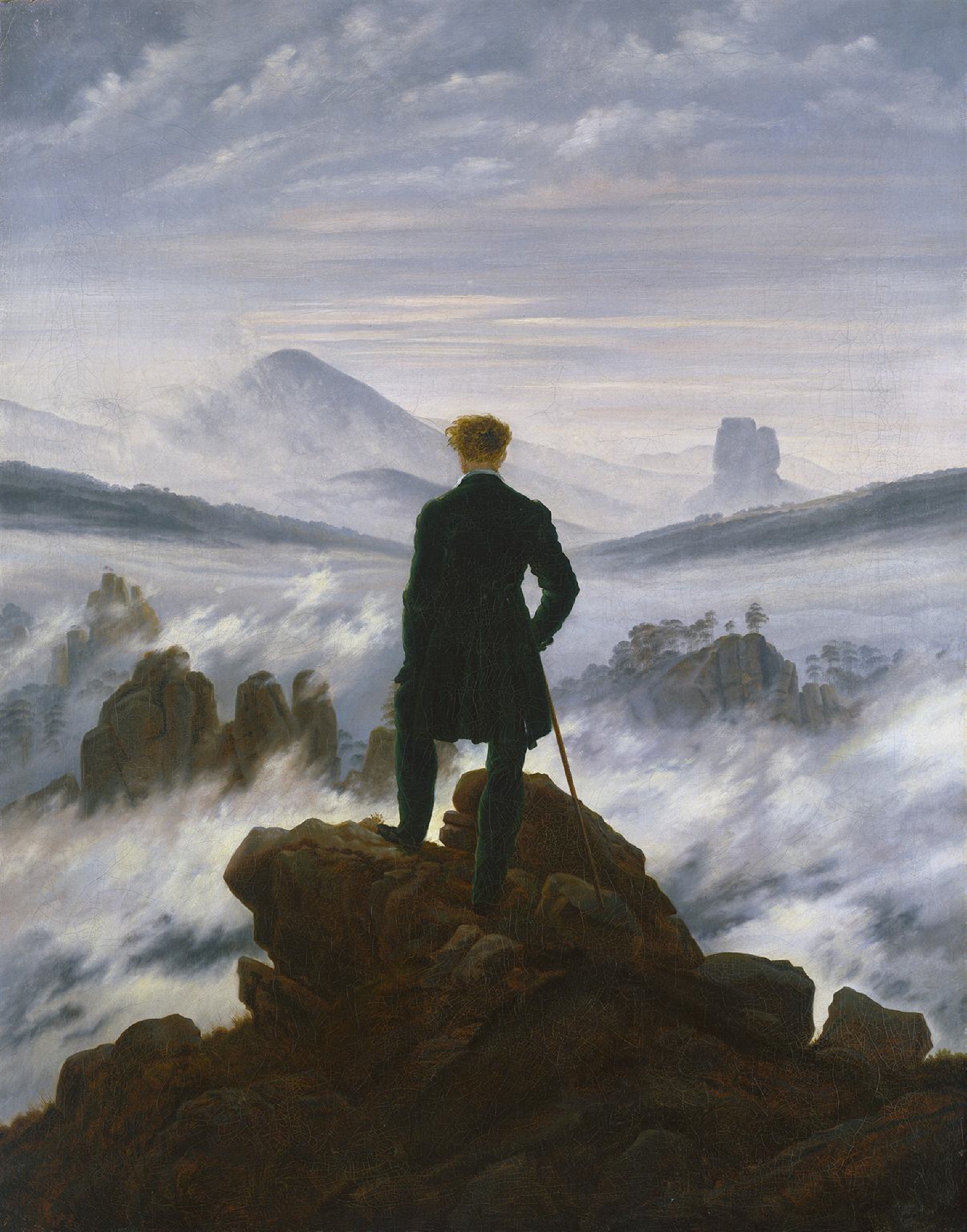

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c. 1817)

Oil on canvas, 37.5” x 29.5”

Hamburger Kunsthalle, HK-5161

Friedrich was one of the preeminent German Romantic painters during the first half of the nineteenth century, and this work is one of his most admired. Although it is true that the work inspired positive Western attitudes toward mountaintop hiking, there is more going on here than an appreciation of natural beauty. Friedrich believed that his art should be more than a faithful retelling of the world, that it should also portray an artist’s introspection. The hiker in the foreground wears traditional German clothing, a political statement Friedrich made throughout many of his paintings. His gaze to the misty landscape below evokes an inescapable uncertainty.

Vincent Van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889)

Oil on canvas, 28.875” x 36.75”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.132

Van Gogh painted this work at the location where he encountered this scene in the south of France. In painting this real place, Van Gogh recreated the scene with thick strokes and bright curves to freeze the wind into his painting and to retell the emotional effect of the scene. Cypresses were common in many of his works, including perhaps his most famous Starry Night. To Van Gogh, these obelisk-like trees were highly symbolic. At times, they represented death as a connection to the afterlife, while at others, they represented isolation, a feeling Van Gogh was all too familiar with. That there is a pair of cypress trees may represent the artist’s dependence on his faithful brother, or his own dual personality.

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow (1836)

Oil on canvas, 51.5” x 76”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 08.228

Cole was the most influential member of the Hudson River School, a loosely-tied group of American landscape painters. He first tried his hand at history painting before moving on to landscapes, which were considered inferior at that time. Cole sought to make his landscapes as full of meaning as history paintings, and The Oxbow is a prime example of his success in doing so. Cole transformed the post-storm Connecticut River valley into a statement on American expansionism through his juxtaposition of the wilderness, battered by the storm, with the unscathed farmland below. Cole hints at his answer to whether Americans should move west by painting himself into the picture.

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon (c. 1825–1830)

Oil on canvas, 13.75” x 17.25”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.51

Due to his lasting influence and the depth of meaning incorporated into his paintings, Friedrich gets two paintings here. In Two Men Contemplating the Moon, Friedrich and his recently-deceased friend August Heinrich are seen admiring the moon from another mountaintop vista. Unlike most of Friedrich’s work and the other paintings shown here, this landscape is very crowded. The scene is full of meaning: the moon was a respected object among German romantics, here again we see the traditional German clothing representative of German nationalism, the gnarled oak may represent the early death of Heinrich, the moon may represent his purity. Friedrich manages to pack all this meaning into the scene while still preserving its beauty as an imaginary landscape.

No comments:

Post a Comment