Introduction

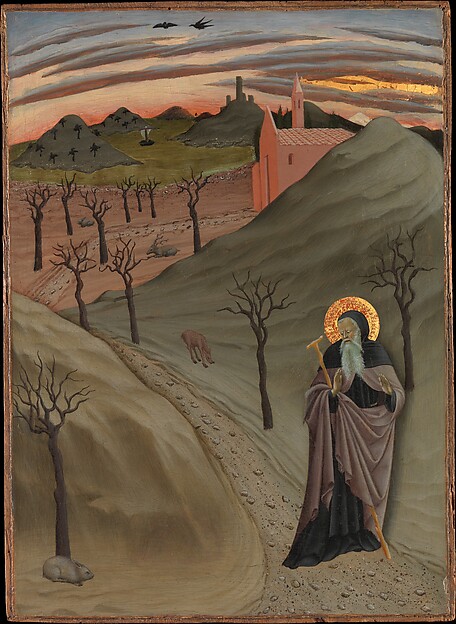

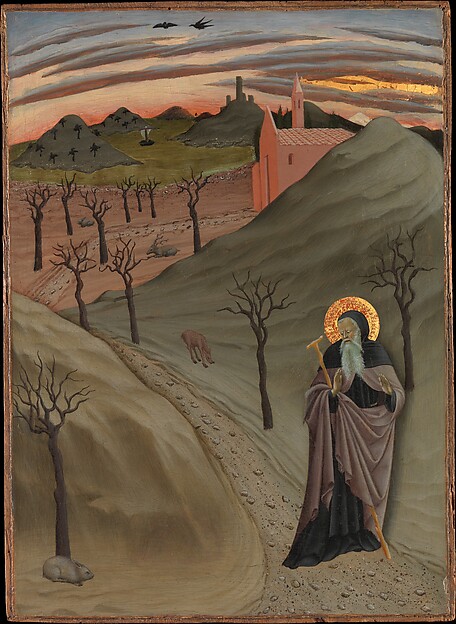

In 1435, Sienese artist Osservanza Master painted Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness. Originally titled Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by a Heap of Gold, the painting depicts Saint Anthony reeling away from a pot of gold which was unfortunately scraped off the painting in its early history. In the painting, Saint Anthony finds relief from the allure of gold in the church behind him. Although long and winding, Saint Anthony is already on the path that leads to the church and the heavenly light that shines down on it. Thus, temptation is overcome when righteousness is pursued. There are, however, a myriad of temptations beyond money by which man may be seduced.

Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness is the centerpiece of this exhibition, which includes pieces featuring exalted figures such as Jesus and Macbeth, as well as normal men attempting to find their place in a world full of glittering attractions. Some, such as the recurring Saint Anthony, find repeated salvation from temptation through Godly faith. Other men are shown in the throes of wickedness after having been seduced and eventually even defined by that which first tempted them. Mankind’s relationship with temptation is perhaps the most unifying experience we share. This exhibit will focus on how artists throughout history have depicted man’s relationship with temptation.

Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness, Osservanza Master, ca. 1435, Tempera and gold on wood, 1975.1.27

Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness focuses on Saint Anthony’s temptation by a pot of gold, which is no longer shown. The viewer is given assurance in Saint Anthony’s victory by the path that leads to the church in the background. The matching golden tones of Saint Anthony’s halo and the heavenly light above the church further confirm that Saint Anthony finds his riches not in earthly gold, but in the rewards of faithfully following God.

Christ in the Wilderness, Moretto da Brescia, ca. 1515-1520, Oil on canvas, 11.53

Twenty years before Osservanza Master’s piece above, Moretto da Brescia painted Christ’s own temptation in the wilderness. Brescia focuses his paintings on the words of Mark 1:13, “and He was in the wilderness forty days, being tempted by satan. He was with the wild animals, and angels attended him” (NIV). Christ in the Wilderness points back to the Garden of Eden, where Adam was surrounded by tame creatures and still succumbed to temptation. Despite Christ’s more dangerous environment, he of course succeeds in resisting earthly temptations with the aid of several angels. Osservanza borrowed from Brescia’s work by also surrounding Saint Anthony with dangerous animals in the wilderness.

The Temptation of Saint Anthony Abbot, Master Osservanza, ca. 1435-1440, Tempera on panel, Yale University Art Gallery, 1871.57

Master Osservanza actually painted an entire series on Saint Anthony’s travels and temptations. This one, painted sometime shortly after Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness, shows the attempted seduction of Saint Anthony by a demon disguised as a women. We have a further link to our centerpiece painting in the doorway that Saint Anthony is fleeing to, which we know to be the church by its identical coloring and design. And so a godly man finds, in his religion, victory over both greed and the passions of the flesh.

The Temptation of Saint Anthony, Salvador Dali, 1946, Oil on canvas, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium

In 1946, Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali painted his own interpretation of Saint Anthony’s temptation. One of the most notable differences to earlier interpretations is the strong, obvious imagery between Saint Anthony, the means of his salvation, and his temptations. Saint Anthony has traded his lovely robe and halo, and upright posture, for a now humiliating depiction on his knees, bent over and naked. Rather than symbolized as a distant church, Saint Anthony’s God is now raised over his head in the form of a cross, as the only possible means of victory over the earthly temptations that tower overhead, threatening to crush him. The viewer feels the action and impending calamity of the monstrous horse bringing its weight down to destroy Saint Anthony.

Macbeth Instructing the Murderers Employed to Kill Banquo, George Cattermole, ca. 1850, Watercolor Painting,Victoria and Albert Museum, 1015-1873

This is the first painting of the exhibition to show defeat, rather than victory, over temptation. From Act 2, Scene 1 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the painting shows Macbeth instructing assassins to kill Banquo and his son because they are a threat to his reign. Note that Macbeth has already murdered King Duncan to assume the crown. Macbeth is the main figure of the painting, seated on a massive throne and leaning over his ragged killers. Cattermole strays from the literal scene by hiding the Three Witches behind his throne, gleefully watching Macbeth spiral farther down the evil path they have tempted him onto. The Witches have no need to take an active role in this scene, because after initially seducing Macbeth into evil he never considers changing his ways. For Macbeth, his mistakes prove fatal.

Armed Robbers, Oklahoma City, Larry Clark, 1975, Gelatin silver print, 1994.373.3

This photograph by Larry Clark shows two young men, proudly sporting pistols and cigarettes. The photo examines Clark’s personal relationship with temptation, and even glorifies the vices that Clark never enjoyed in his youth. Raised in postwar, strait-laced 1950’s America, Clark both feared and envied the wrongdoing that the next generation of American’s had fallen into. He recognized the romantic allure of being bad, smoking cigarettes and shooting guns. Without a means to defend themselves from worldly temptations, Clarke’s robbers are not only caught up in sin, they’re defined by it.

No comments:

Post a Comment